A cultural renaissance swept the Arab world from 1900 to 1948, forever changing the meaning of storytelling in Palestine, as illustrated by scenes showing children gathered around a storyteller’s Box of Wonders, a Hakawati recounting the mythic Arab hero Abu Zayd al-Hilali nearly killing his estranged father, and the mischievous shadow puppet Karagoz bungling yet another get-rich-quick scheme.

Karagoz in the village square

The village square was the birthplace of drama, where scenes of daily life unfolded for centuries across towns and villages in Palestine. In coffeehouses and at religious festivals, hakawati storytellers enthralled crowds by dramatically recounting folkloric tales and the adventures of mythic heroes. The vulgar fool Karagoz was especially beloved among young and old in Jerusalem. Rude and rough-spoken, he knew he was a fool, directing jokes at his own stupidity. As Arabic literature professor Mas’ud Hamdan described, Karagoz was “a fool with a high degree of self-consciousness.” On stage, his constant companion was the arrogant, cold-hearted puppet ‘Aiwaz, who was forever trying in vain to “refine” Karagoz. During Ramadan, shadow puppet shows were traditionally performed twice nightly, with local puppeteers competing with visiting Arab performers. But as Western-style theater and cinema emerged in the early 1900s, these scenes became increasingly rare. “The theater silenced the storyteller,” laments Palestinian cultural activist Serene Huleileh, who works to revive the art of the hakawati.

Hamlet in Gaza

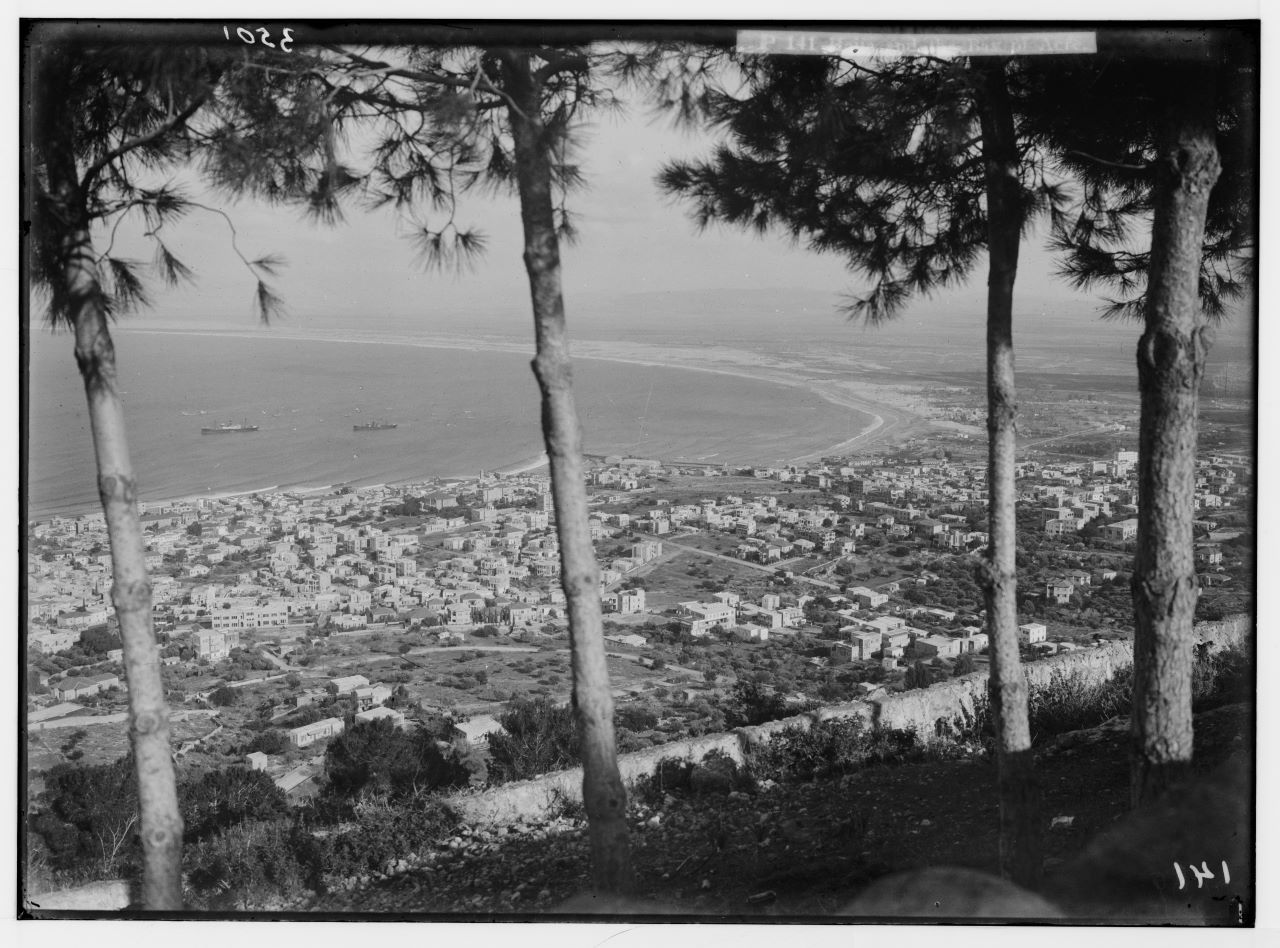

In 1911, Hamlet stepped onto the stage for his first-ever performance in Gaza. At the time, many of the plays that were performed were translated works originally written in English or French and most theater in Palestine was non-professional and amateur. Influenced by the Arab cultural revival (al-Nahda) of the time, and especially the Egyptian cultural scene, an interest in Western-style theatre began to emerge. In Jerusalem and Haifa, young poets, writers, and dramatists were invited to read their works in literary salons.

And when Palestine’s first radio station began broadcasting in 1936, the director of the station’s Arabic programs, the famed poet Ibrahim Touqan, encouraged playwrights and actors to perform their work on air. The first play to be broadcast on the Palestinian Broadcasting Station was an interpretation of the story of Samson and Delilah written by the Jerusalemite playwright Nasri al-Jawzi.

The first actresses

Long before the rise of the theater, the women of Palestine were experienced storytellers who recited tales to each other and to children, but only in the private spaces of their homes. However as theater performances became more popular, a number of pioneering women started to perform in public as theater actresses.

Because actresses were few and far between, female characters in translated plays were often converted to male characters or else they were portrayed by men dressed and made up as women. According to the playwright Nasri al-Jawzi, the biggest obstacle faced by theater troupes at the time was “finding an educated, well-mannered girl who would agree – whose family would accept that she – get on stage and act out the romantic roles required by the theater.” Things became easier in the mid-1930s, after the Palestinian Broadcasting Station was established because women actresses did not have to appear before a live audience and could use stage names instead of their real names.

One of the earliest actresses was an unnamed Argentinian woman of Arab descent who spoke Arabic with a heavy foreign accent. Al-Jawzi also tells the story of an actress who took on the role of the romantic heroine in a play during the early 1930s. During rehearsals, whenever the male lead would approach her to declare his love, she would tell him not to come any closer and warn him that there would not be any kissing. On the evening of the performance – in a theater packed with people – when her love interest walked towards her on stage, she unexpectedly yelled “Don’t come closer, there won’t be any kissing!” And from the dark rows of the audience, a man yelled out “It’ll be left until later!” since the male lead was – in fact – her real-life fiancée.

Does it matter where you tell a story? If you perform it on the radio or recite it in the street on a warm Ramadan night? The demise of popular storytelling culture and the development of formalized theater in Palestine is often presented as progress, a development from naïve folk art to sophisticated high art. This is a view taken by many, from Israeli academics who study Palestinian theater such as Reuven Snir to Palestinian dramatists such as Nasri al-Jawzi.“It shows us another level of freedom and creativity. The storyteller doesn’t have to have a stage, or knowledge of Western art, or even props. Sometimes he only has his presence.”

But not everyone agrees. Samar Dudin is a theater director who sees the old forms of storytelling as much more than a mere performance of folktales. “This type of storytelling is based on improvisation,” she says, adding that “It shows us another level of freedom and creativity. The storyteller doesn’t have to have a stage, or knowledge of Western art, or even props. Sometimes he only has his presence.” To her what was special about the hakawati was his freedom, the lack of restrictions on how he tells his story. Because of this, she sees these storytellers as existing outside the confines of society’s moral values and of political power structures.

“It shows us another level of freedom and creativity. The storyteller doesn’t have to have a stage, or knowledge of Western art, or even props. Sometimes he only has his presence.”

In the words of the cultural activist Serene Huleileh, “There is something democratic about storytelling. The hakawati is free. He can go anywhere and speak to whomever.” She adds, “Anyone can tell stories. You don’t need a degree, or approval from the censor to tell your story.” Huleileh points out that in the storytelling tradition, the audience plays an important role when they interact with the hakawati, unlike in traditional Western theater where the audience is passive. It is only in more contemporary, experimental forms of Western theater that audience involvement and improvisation have emerged as important.

“They say theater is the father of the arts,” Serene Huleileh tells us, “but storytelling is the mother of the theater.”

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Snir, Reuven. “Palestinian theatre: Historical development and contemporary distinctive identity.” Contemporary Theatre Review 3, no. 2, 1995, pp. 29-73.

- Hamdan, Mas’ud. Poetics, Politics and Protest in Arab Theatre: The Bitter Cup and the Holy Rain. Sussex, Sussex Academic Press, 2006.

- Snir, “Palestinian theatre,” pp. 29-73.

- Hamdan. Poetics, Politics and Protest in Arab Theatre.

- Ibid,p.

- Snir, “Palestinian theatre.”

- Hamdan. Poetics, Politics and Protest in Arab Theatre.

- Samar Dudin and Serene Huleileh. Interview by Thoraya El Rayyes, Amman (2015), sound recording.

- Al-Jawzi, Nasri. Tarikh al-Masrah al-Filastini, 1918-1948 [The history of Palestinian theatre, 1918-1948 ]. Cyprus, Sharq Press: 1990..

- Snir, “Palestinian theatre.”

- Samar Dudin and Serene Huleileh. Interview by Thoraya El Rayyes, Amman (2015), sound recording.

- Ibid.

- Snir, “Palestinian theatre.”

- Al-Jawzi. The history of Palestinian theatre.

- https://www.palmuseum.org/