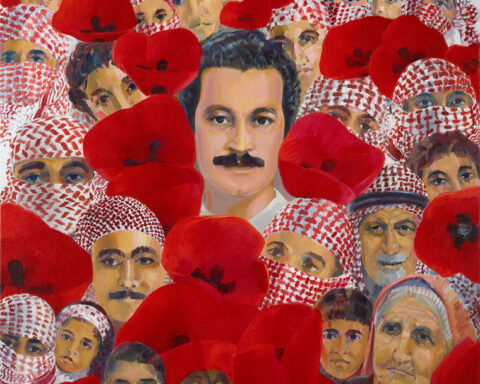

A Palestinian Artist’s Journey of Resilience and Advocacy Born in the vibrant city of Haifa, Palestine, in February 1942, Abed Abdi’s artistic journey is deeply intertwined with the tumultuous history of his homeland. Forced to flee his home during the violent events of the

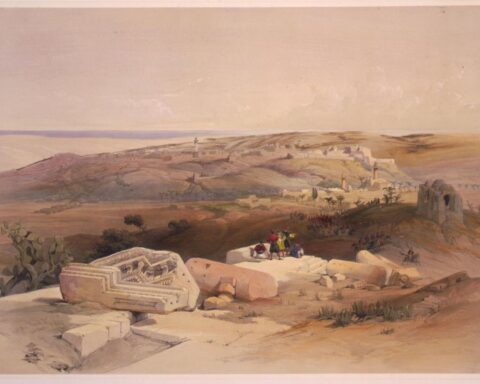

Continue ReadingBefore the catastrophe of 1948, Palestine witnessed widespread economic prosperity, with a decrease in poverty and unemployment rates, an increase in GDP, and an improvement in individual income levels. This placed Palestine

GoIsraeli Forces Intensify Attacks on Jabalia, Targeting Schools and Shelters In recent escalations, the Israeli occupation has intensified its artillery and air strikes on the town of Jabalia and the Jabalia refugee

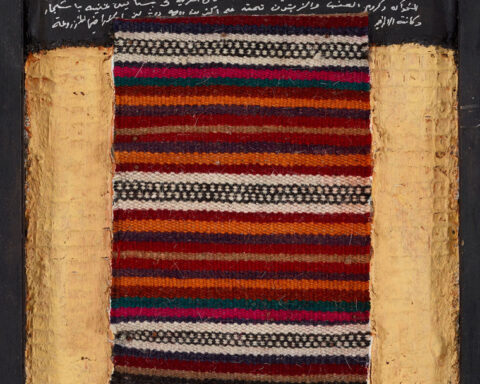

GoAbdulhay Musallam Zarara, born in 1933 in the village of Al Duwayma, Palestine, emerged as a self-taught artist whose profound works encapsulate the historical struggles and enduring traditions of the Palestinian people.

GoSamia Halaby, a leading abstract visual artist, has not only pushed the boundaries of abstraction but has also contributed significantly to the understanding of art’s intersection with culture and society. Born in

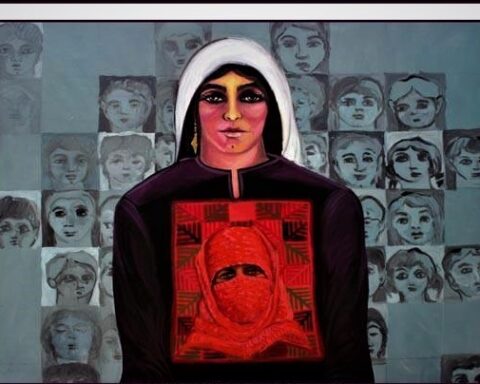

GoLaila Shawa, a prominent artist born in 1940 into a wealthy Gazan family, embarked on a remarkable journey that intertwined her passion for art with a fervent commitment to social and political

GoAbdelrahman Al Muzayen, born in 1943 in Qubayba, a village in the Ramle subdistrict of Palestine, lived a life dedicated to preserving Palestinian culture and history through his art and activism. After

GoMohammad Al-Hawajri, was born at the Bureij Refugee Camp in the Gaza Strip in 1976. In 2002 Al-Hawajri founded the Eltiqa’Group for Contemporary Art in the Gaza Strip. Between 2008 and 2009

GoMaher Naji, showing the Palestinian olive harvest via Palestine Museum (US)

GoWhile cartoonists might not always receive as much attention as other artists, they play a crucial role in conveying political and social messages through humor and satire. Here are a few prominent

Go