Palestine boasts a rich and extensive history. Initially recorded as Peleset in ancient Egyptian tablets over 3000 years ago, the region between the Mediterranean and the river Jordan holds diverse significance for various peoples. Over the centuries, Palestine has been a melting pot for numerous cultures, kingdoms, and empires, including the Assyrian, Nabataean, Persian, and Roman civilizations, among others.

These influences have left a lasting impact on the language, vocabulary, and place names used by the indigenous Palestinian population.

Even agricultural practices in Palestine can be traced back to the Natufians, who are credited with the invention of agriculture and inhabited the region as early as 9,000 BCE.

It is crucial to clarify that when discussing Palestine, we are not referring to a Palestinian nation-state, as the concept of a nation-state was largely absent throughout history.

It is important to avoid imposing modern notions onto historical contexts where they do not apply.

The idea of an unchanging, well-defined, and homogeneous ancestral group with exclusive territorial ownership is a myth propagated by reactionary ethno-nationalist ideologies.

As in other regions, kingdoms rose and fell, religions were established, and wars were waged throughout Palestine’s history.

This article does not aim to delve into the specifics of Palestinian history, as entire books have been dedicated to the subject. Instead, the goal of this introduction is to provide the political context leading up to the modern Palestinian question.

After the Mamluks were decisively defeated in the battle of Marj Dabiq in 1516, the Levant became accessible to the conquering Ottoman armies. A few months later, they would seize Jerusalem, marking the beginning of one of the longest eras in Palestinian history, lasting over 400 years. Jerusalem held great significance for the Ottomans due to its religious and historical importance. They initiated grand construction projects from the start of their rule, shaping the architecture and landscape of Jerusalem, notably the impressive walls erected by Suleiman the Magnificent. Throughout its history, the Ottomans organized Palestine into various political structures. In 1887, the region was divided into three districts (Sanjaks): Jerusalem, Nablus, and Acre. The Sanjak of Jerusalem held such importance to the Ottomans that it was directly governed by Constantinople (later Istanbul).

The combined population of these three areas was roughly 600,000, with the large majority being Sunni Muslim. Palestinian Christians accounted for about 10 percent of the population, while there were approximately 25,000 Jewish Palestinians, primarily located in Jerusalem, Hebron, Safad, and Tiberius. The Ottoman Millet system and its various forms granted some level of autonomy to minority religious and ethnic communities. Although this system had its flaws and its tolerance fluctuated under different governors and social and economic conditions, it was still preferable to the persecution and pogroms experienced by various religious groups in Europe. Relations among the diverse religious groups in Palestine were generally stable and peaceful, forged through over a millennium of coexistence and shared challenges. For instance, the inscription on the Jaffa Gate of Jerusalem acknowledges Christian and Jewish Ottomans, who like Muslims, are considered part of an Abrahamic religious tradition. Palestinian Muslims also celebrated religious festivals in honor of Jewish prophets and holy men, such as Reuben, son of Jacob. This inclusive attitude extended to Christian Palestinians, as seen in the tradition of a Muslim family being entrusted with the keys of the Holy Sepulcher. However, as with any empire, there were periods of peace and prosperity as well as times of hardship and conflict. Towards the end of the Ottoman Empire, the latter became more prevalent. With the rise of European-style nationalism and the weakening of the Ottoman state, relations between ethnic groups and communities began to deteriorate. Rebellions against Ottoman rule occurred, and although Palestine briefly gained autonomy under the leadership of Daher al-‘Umar, it was eventually suppressed by Constantinople. These tensions were further intensified by the Young Turk Revolution and the efforts to Turkify the Ottoman provinces. The empire eventually collapsed after its defeat in World War I, leading the various peoples who made up its population to seek independence and their own nation states. However, these aspirations were hindered as the peoples transitioned from the dominance of one empire to the dominance of others. It was during the final decades of this collapse that Theodor Herzl, an Austro-Hungarian thinker, began laying the groundwork for a new political movement that would ultimately alter Palestinian history.

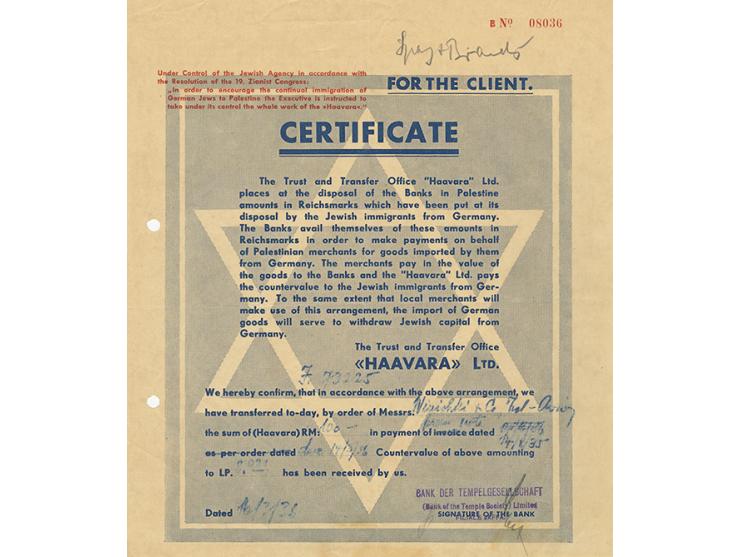

The inaugural Zionist congress, held in Basel in 1897, brought together 200 delegates from across Europe. The congress aimed to establish a Jewish state in Palestine and coordinate the settlement of Zionists in the region. Herzl, the founder of political Zionism and president of the congress, viewed this as the solution to the “Jewish question,” providing emancipation from persecution. While prior Zionist and proto-Zionist movements had settled in Palestine, such as Hibbat Zion, the congress was the first to effectively organize colonization efforts in a centralized manner. Zionism is a political movement advocating for a Jewish nation-state in Palestine with a Jewish majority. However, the land was already inhabited, leading to discussions on the fate of the native Palestinian Arabs. The consensus among early Zionist discussions was that they needed to be somehow removed, either through agreement or force, to establish a Jewish majority state. The term “settler-colonialism” refers to a specific phenomenon where settlers seek to establish a new homeland for themselves. Unlike classic colonialism, settler colonialism initially relies on an empire for support and often involves settlers fighting against the sponsoring empire. Additionally, settlers are not only interested in the resources but also the lands themselves. Early Zionists openly acknowledged their movement as a form of colonialism. This is evident in Herzl’s correspondence with Cecil Rhodes and Jabotinsky’s essay, “The Iron Law.” The establishment of the first Zionist bank as the ‘Jewish Colonial Trust’ and the support from organizations such as the ‘Palestine Jewish Colonization Association’ and the ‘Jewish Agency Colonization Department’ further underscore this viewpoint.

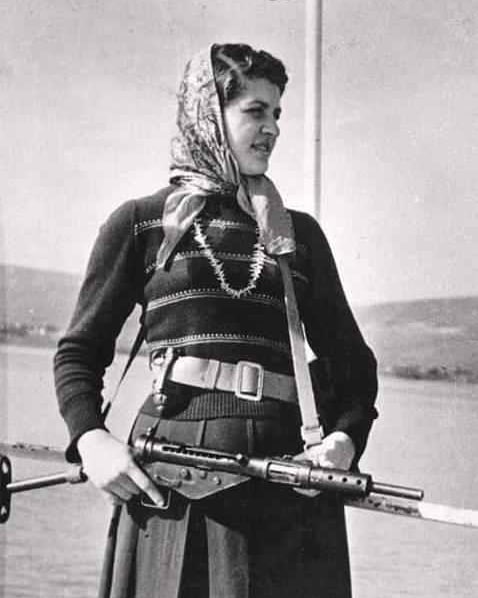

The Zionist movement would soon start sending settlers to Palestine and establishing a presence with the aim of seizing control of the entire region. The Ottoman Empire’s defeat in WW1 and Palestine’s transition to British mandate presented the perfect opportunity for them to achieve these objectives. More details about this will be covered extensively in the upcoming introductory article.

Following its defeat in WW1, the Ottoman Empire was dissolved, and its territories were divided among various European colonial powers. The British took control of Palestine and Jordan, while Syria and Lebanon fell under French mandate. The British officially declared Palestine a mandate in 1922, categorizing it as a ‘Class A’ mandate, indicating it was provisionally independent but still under the control of the allied forces until it was deemed ready for full independence. The mandate of Palestine presented an opportunity for the Zionist movement to advance its goals, as the British were more receptive to their objectives than the Ottomans had been. The Balfour Declaration, issued by the British government, promised the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. Despite this declaration, the British were not motivated by altruism but rather by their own interests in the region. Empowered by the Balfour Declaration and support from the British, the Zionist movement intensified its colonization efforts and established a provisional proto-state in Palestine called the Yishuv. With explicit and tacit sponsorship from the British, the Zionists were able to expand while the British harshly repressed Palestinian movements. This ultimately led to the conquest and destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages and neighborhoods by the end of the mandate. These circumstances and events led to the establishment of Israel through the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians and the erasure of their society. The next article will delve into Zionist aspirations, partition, the final years of the mandate of Palestine, the 1948 war, and the Nakba – the original sin of Israel’s creation.