In 1930s Jerusalem, a young boy named Hazem Nusseibeh would walk to school through the narrow, stone-paved streets of the Old City. Each morning, as he passed through Damascus Gate, he saw crowds of villagers who had traveled from the countryside. Their faces flushed from the long walk, they carried baskets brimming with grapes and figs to sell in the markets. More than eighty years later, Hazem fondly recalled the lively scenes from his childhood in Jerusalem.

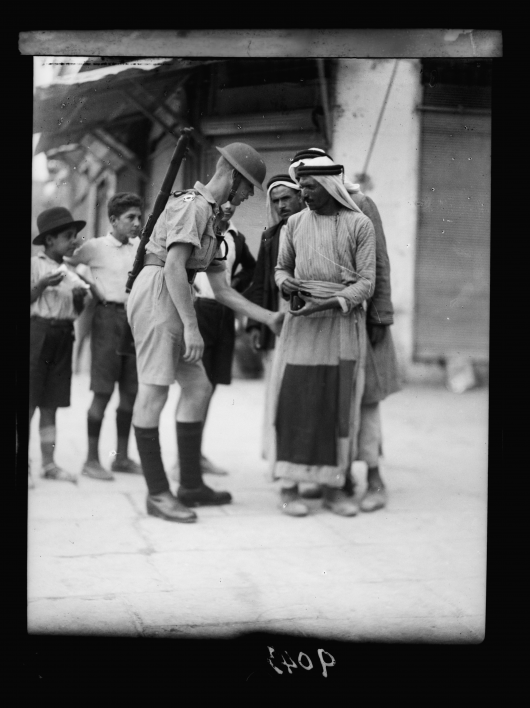

During the 1930s, only about 20% of Palestinian Arabs were literate, so reading newspapers aloud and displaying the images was common practice. The author describes men from villages bringing their harvest to sell at the Old City market. Afterwards, they would gather at coffee shops where someone would read the newspaper aloud as illiterate men looked on, taking in the pictures and cartoons. These communal gatherings allowed illustrated newspapers to spread their message widely, influencing the political awareness of both literate and illiterate Palestinian Arabs.

Drawing the Headlines

After the 1929 Buraq Uprising, British officials sent to investigate the conflict reported back that gatherings where someone read newspapers aloud to illiterate Arab villagers were so commonplace that the fallahin farmers were likely more politically aware than many Europeans.

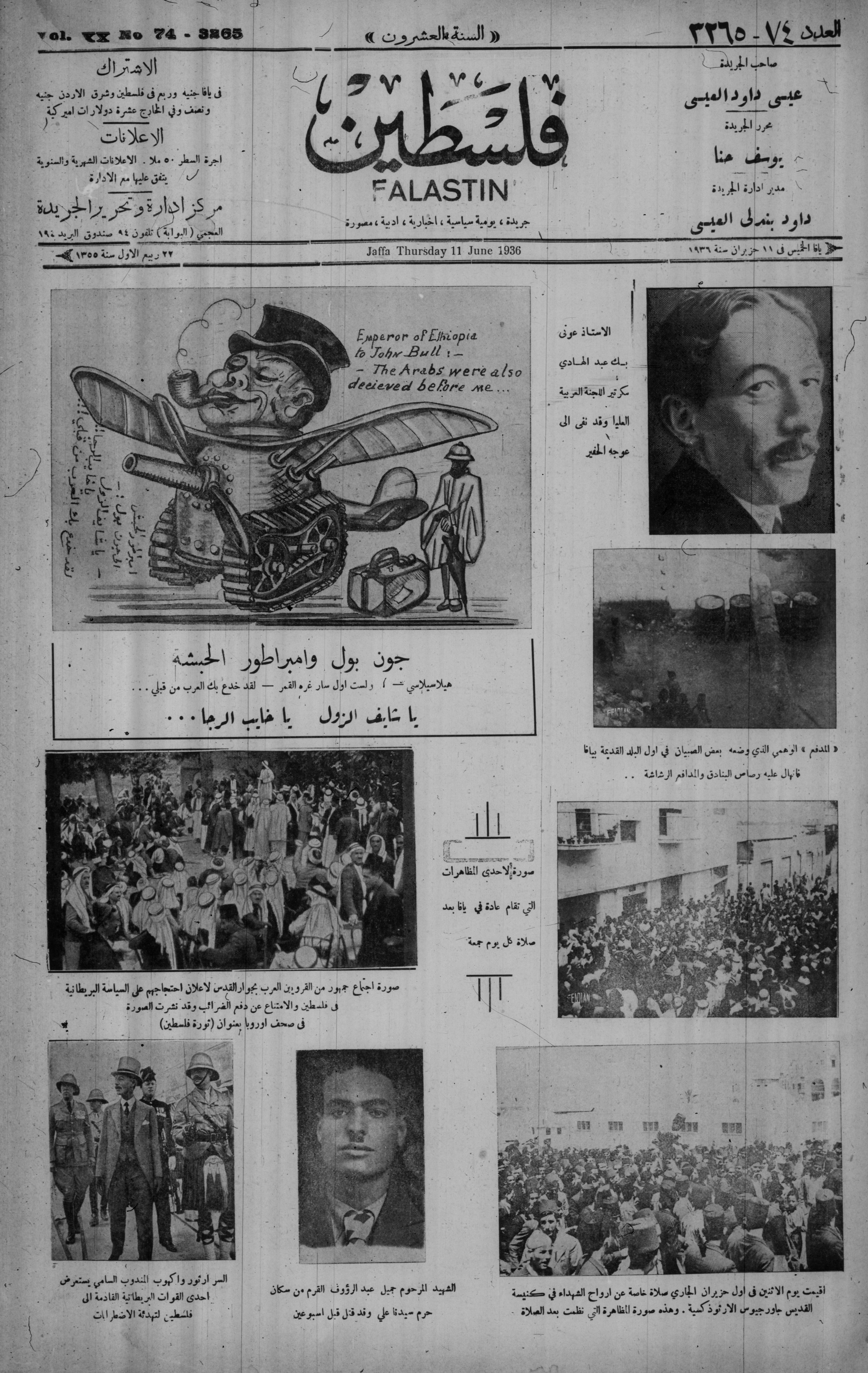

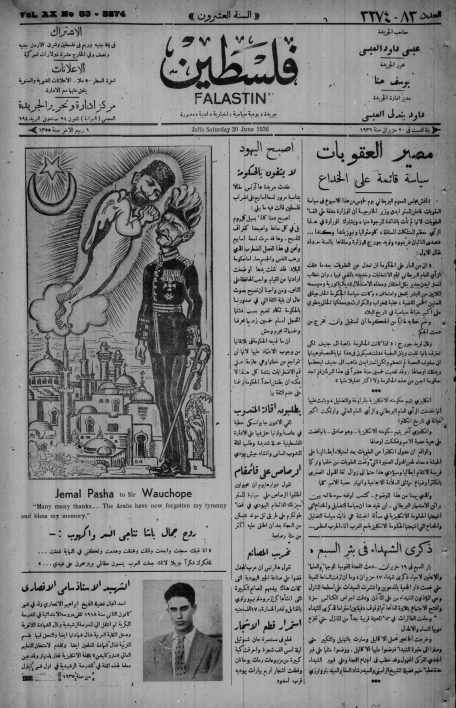

Though the most widely read political cartoons in 1930s Palestine were drawn by a mysterious Christian woman from Eastern Europe, her identity remains unknown. The owner of the Falastin newspaper, ‘Isa Daud al-‘Isa, would conceive of ideas for sharp critiques of political negotiations, tactics, and economic developments, which the woman would draw up as cartoons for the front page. Her story was revealed only decades later, in a serendipitous email from Isa’s son to an American academic shortly before the son’s death. Without this email, the woman’s contributions would have been lost to history.

Sneaking Past Te Censors

At first glance, Palestinian political cartoons seem mysterious in their sudden rise and fall in popularity. Before and after the 1936 Great Arab Revolt, they rarely appeared in newspapers. Yet as tensions escalated in Palestine, the cartoons became more frequent. This rise coincided with increased British censorship of newspapers. The British jailed journalists, banned certain information, and closed papers for “dangerous” articles. During the revolt, Arabic dailies faced over thirty suspensions, while the Jewish press had just thirteen. It appears the conflict fueled both the outpouring of political cartoons and their suppression.

Though seemingly simple and straightforward, some of these political cartoons contained multiple layers of symbolism that allowed subversive messages to evade censorship. For example, the June 1936 Falastin cartoon “The Zionist Crocodile” used imagery to convey a complex narrative about the colonization of Palestine to Palestinian Arabs under repressive British rule.

The bug-eyed crocodile salivates as he prepares to devour Arab fallahin and their citrus groves, his tail emerging from the sea like a ship’s ramp.The crocodile symbolizes early Zionist strategies of colonizing indigenous land through acquisition and bringing European settlers to Palestine by ship. In the accompanying image, a British police officer resembling a bulldog smokes a pipe. His sneering smile matches the crocodile’s menacing grin, suggesting an alliance between the Zionists and British authorities.

In the 1930s, the displacement of fallahin through Zionist land purchases was a pressing economic issue. Fallahin debt and default on credit reached critical levels, made worse by the fact that British had started to tax many previously untaxed pieces of agricultural land. The fallahin resisted by joining trade unions and political organizations, and engaging in civil protest and cultivation disputes directed at the British, Zionists and the Palestinian upper class.

Worth A Thousand Words

At a library in Beirut, a middle-aged man puts on a set of rubber gloves, takes a small reel out of the archive and attaches it to the microfilm reader. The reader is a clunky grey machine that looks something like a PC from the 1980s. The Beirut-based library of the Institute of Palestinian Studies is one of the few places where these caricatures have been preserved, but sadly much else from this period has been lost forever.

Caught up in the fervor of revolt and faced with harsh British repression, it seems Palestinian revolutionaries and their supporters had little time to document their stories and preserve their history. Much of what had existed was lost a decade later in the Nakba, as Palestinians fled their homes in the face of danger from Zionist militias. In these rare drawings, we see some of the few remaining images that tell the story of an anti-colonial consciousness awakening in British Mandate Palestine.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Nusseibeh, Hazem. Interview by Thoraya El Rayyes & Ibrahim Tarawneh, Amman (2015), sound recording.

- Ibid.

- Khalidi, Rashid. The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood. Beacon Press, 2007.

- Shaw, Sir Walter Sidney. Report of the Commission on the Palestine Disturbances of August, 1929: Evidence Heard During the 1st [-47th] Sittings, HM Stationery Office, 1930.

- Sufian, Sandy. “Anatomy of the 1936–39 Revolt: Images of the Body in Political Cartoons of Mandatory Palestine”, Journal of Palestine Studies 37, No.2 (2008).

- Shaw. Report of the Commission on the Palestine Disturbances.

- Sufian, Sandy. “Anatomy of the 1936–39 Revolt: Images of the Body in Political Cartoons of Mandatory Palestine”, Journal of Palestine Studies 37, No.2 (2008), p. 25.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p. 27.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p. 30.

- Ibid.

- Tamari, Salim, and Issam Nassar. The Storyteller of Jerusalem: the Life and Times Wasif Jawhariyyeh, 1904-1948, Olive Branch Press: 2013.

- Sufian. “Anatomy of the 1936–39 Revolt,” p. 30.

- Azoulay, Ariella. “Photographic Conditions: Looting, Archives, and the Figure of the” Infiltrator”, Jerusalem Quarterly, No. 61 (2015): 6

- https://www.palmuseum.org/