The struggle of Palestinian women in the 1920s and 1930s

Latifa Dirbas carries a jug of water on her head from the village of Bal’a, weaving from one mountain to the other while keeping track of the revolutionaries. Meanwhile, Umm Wedad Arouri leaves her village of Arura to Saffa, then to Birzeit, then to Ramallah, where she delivers an oral message to the rebels there. She answers their questions, describes the means of transport, and gives them supplies, telling them where the weapons are located. British soldiers stop Latifa on her way, but she tells them she’s only going to fetch some coal.

Latifa and Umm Wedad were not alone in their actions. Women played a key role in supplying, informing, and financing the Palestinian Revolution. Women from villages sold their jewelry, while women in cities used their inheritance money to pay for the Revolt.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the entire Palestinian family was affected by colonial policies. But if only historical documents are observed, one will note the marked absence of women in this period, whether it be socially, economically, or in struggle. Even so, the Palestinian narrative before the Nakba will remain incomplete without examining and understanding the role of women in the struggle against colonialism.

Although colonial regimes have often claimed to champion women’s liberation, supposedly aiming to spread “freedom and justice” to marginalized groups, even cursory scrutiny will reveal the spuriousness of such claims. Often, colonialism limited the parameters for women’s emancipation, under the pretext of respecting local society, customs, and traditions..

But Palestinian women did not need colonialism to justify their actions. They fought in their homes and in the streets. They resisted colonialism politically, economically, and ethically. And quite crucially, they played an instrumental role in guerilla warfare by supporting the male fighters—as carriers of information, keepers of secrets, and smugglers of weapons. Their role in uplifting morale only bolstered such tasks.

From mountain to mountain I will carry your weapons

After the First World War, the Palestinians suffered major economic setbacks. Palestine had served as a battleground, leading to the damage of infrastructure, the exacerbation of an already harsh famine resulting from a locust plague, and subsequently, a drop in population. The devaluation of the currency and the disruption of the economy all added to the worsening conditions.

In those circumstances, the British Mandate imposed employment laws that granted jobs to the petty bourgeois class at the expense of other classes. Education was neglected, garnering only 5% of budget allocations. At the end of 1927, the number of schools for boys was fifty-three, compared with only four schools for girls. This reflected the absence of women in colonial thinking, despite the slogans calling for their liberation. The colonial masters cynically blamed this absence on the attitudes of local society. This was the same justification the British used to grant women unspecialized jobs, claiming for instance that there were no qualified “Muslim female teachers” capable of working in rural areas. But the “efficiency” of rural women surpassed colonial expectations.

Rural women shared an intimate relationship with weapons. They would take care of weapons as if they were their own children—cleaning them, maintaining them, and hiding them in the fields. When the army attacked her village, Umm Ahmad hid the gun inside her dress before burying it in a potato field. After collecting some potatoes to cover up her act, one of the English soldiers mocked her and asked: “What are you doing?” Umm Ahmad replied: “I am taking these” – she held up the potatoes- “to feed him”- and pointed at her child. “Is that it?” the soldier asked. “That’s it,” she insisted.

Women were trained in handling and firing weapons. Zakia Huleileh recounts how she was taught in operating the Sten and Tommy Guns, two English-manufactured machine guns. She found them hard to carry, but her brother would encourage and teach her: “he would place a rock as a target and tell me: shoot!”

According to Hassna Masoud, the women of Tirat Haifa and Ramin were known for carrying weapons and fighting:

“When the guards of Abd al-Rahim al-Hajj Muhammad were captured, the women came out and fired at the English, to make them think that they had apprehended the wrong fighters.”

This was verified by Sabha Yacoub from Ramin.

The women played an important role in concealing weapons within their loose clothing, becoming a means of transport which fueled the logistics of the revolution. Fatima al-Khatib from Ain Bait al-Ma’ recalled how she would hide weapons in her “bosom,” or in the fireplace, where she would “pile manure over it”.

Women also played a coordinating role with the rebels to secure food supplies for besieged villages. When the British army besieged Baqa al-Gharbiyya, the soldiers rigged the bridges and roads leading to it with mines to cut supplies for villages and rebels. The women did not stand idly by when hunger threatened entire villages. They coordinated with the rebels, who raised white flags on the safe roads in order for women to reach the besieged villages safely.

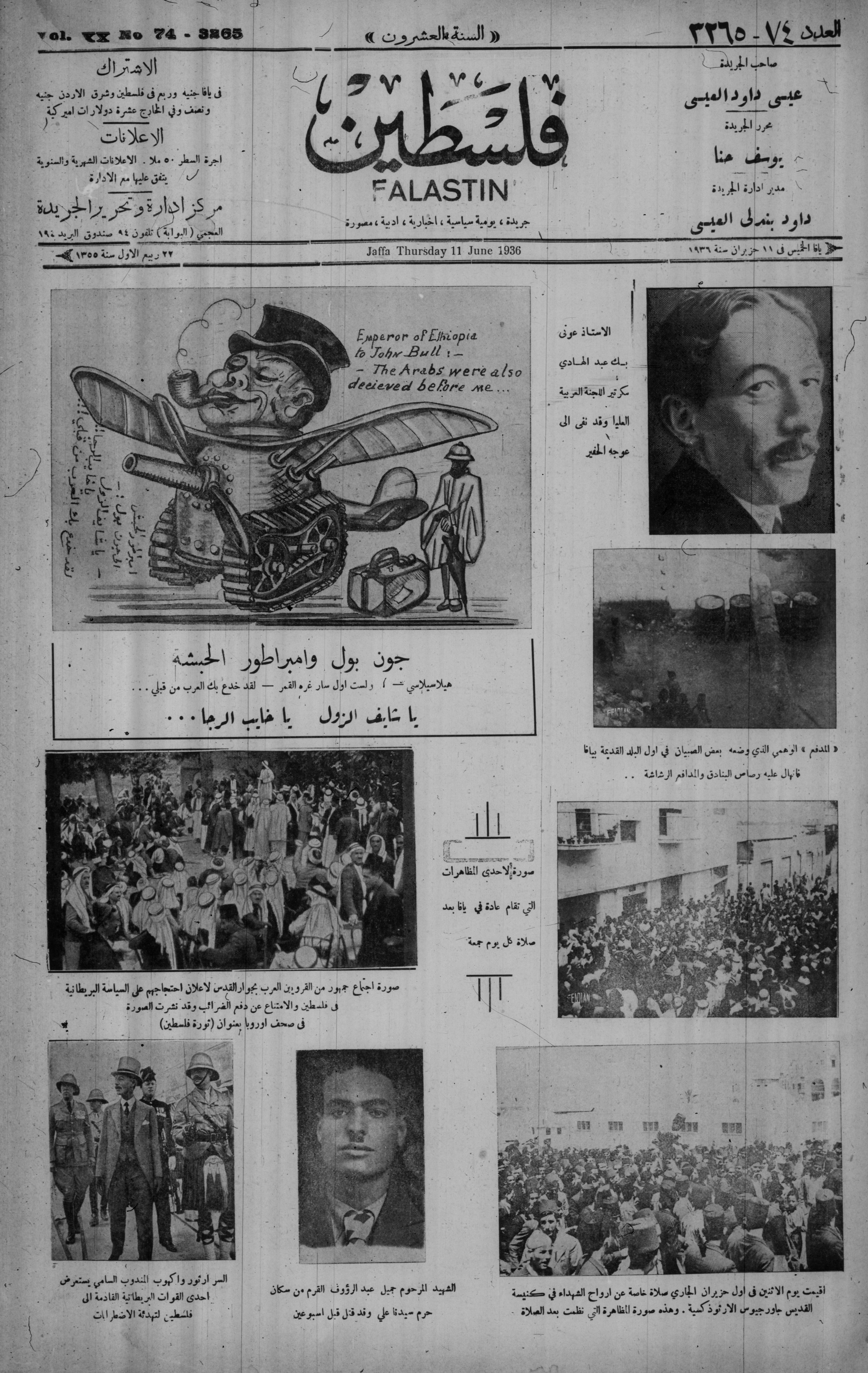

Women and the High Commissioner

Tarab Abdul-Hadi, one of the pioneers of the Palestinian national movement, lived in a small house East of Jerusalem during the British Mandate. From this house began the movement of a silent convoy of cars, which passed through the city of Jerusalem, and ended with a speech in front of the High Commissioner’s headquarters. A list of demands from the demonstrators was presented to him. This took place immediately after the first women’s conference was held in October 1929, with the participation of 300 Palestinian women.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY